|

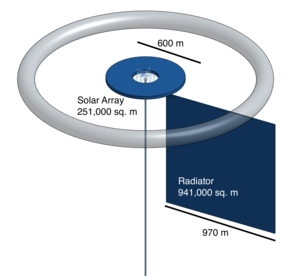

| Fig. 1: Colony Configuration. [1] (Courtesy of NASA. Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

The Stanford Torus was a concept space colony designed in by a group of researchers, scientists, and educators during the summer of 1975. [1] The exploration of space colony design was in response to the growing concerns around the energy requirments to support human life and activities. Gaucher's 1965 analysis and predictions of human energy consumption suggested that the energy needs for human civilization would grow drastically through to 2200. [2] As world energy consumption grew, it would become more important to develop technology to harness new forms of energy, with a heavy emphasis on solar energy production. In 1968, Glaser proposed solar power stations as a means to tap into solar energy. [3] These solar power stations would collect solar energy and beam it back to earth. This was proposed with the intent to enable space power companies, which would sell energy to residents on Earth. In order to build and manage these solar power generators, space colonies were designed as habitats for workers.

Although the idea of space colonies still live in the realm of science fiction, many minds worked to understand the feasibility of creating large habitats to sustain human life in space. One key question for the creation of space colonies like the Stanford Torus is how much energy would be required to sustain a high quality of life? While the total energy analysis of a space colony would be quite intensive, I would like to use this article to explore some simple estimates of the energy requirements of the Stanford Torus. The primary goal is to begin to undestand the scale of energy generation, the scale of waste heat management, and the general feasability of powering a space colony. I will build off the energy estimates proposed in the 1975 report while making some adjustments and exploring some what-if scenarios based on the current state of technology.

The Stanford Torus was designed to house 10,000 people. It was to be a fully self-sufficent colony with the capability to produce food, support manufacturing, and enable high quality residences for its inhabitants. The colony, shown in Fig. 1, is designed as a torus with a diameter of 1.8 km. The habitat tube has a diamter of 430 m. The torus rotates at 1 revolution per minute to create artificial gravity. A stationary mirror at 45° is used to redirect sunlight down to the colony. The inner disk of the torus acts as a docking bay and solar generation area. 10 km away from the station is a tethered solar power generation satellite. This satellite provides the remainder of the power required for the colony that is not generated in the inner disk. A large, flat stationary radiator sits below the inner disk and acts to dissapate waste heat from the station.

|

| Fig. 2: Solar panel area vs. cell efficiency. (Source: N. Martelaro) |

All energy on the Stanford Torus was assumed to come from solar power. Pure sunlight would be used for agriculture, illumination, and heating of the internal habitat. Solar power generation using photovolatics would be used to generate electricity. This electricity would be used for daily living, such as household appliances, interior lighting, and personal mobility, and for industrial processes such as running electric motors and pumps for agriculture, sanitation, and manufacturing processes.

In the original report, the Stanford Torus team estimated electrical energy production to be 3kW per person. This estimate was derived from doubling the per capita electricity consumption of Americans in 1975. Given 3 kW per person, the total energy required would be 30 MW. Using an estimate of 1390 W per square meter of solar energy available in space and a 10% efficient solar cell, the Torus would require a minimum solar panel area of 215,827 m2.

While per capita energy requirements are nearly the same today as in 1975, ~1.5kW per captia, the efficieny of solar panels has improved. Currently, commercial solar cells can reliably attain ~22% efficiency. [4] Assuming a 22% conversion efficiency decreases the required solar cell area to 98,100m2, about 54% less area than required at 10% efficiency. Fig. 2 shows a graph of reducing area requirments as a function of cell efficiency. Note that we have already realized much of the area reduction from 1975 with current technology. This being said, any further efficiencies will help to reduce material usage. This is important as energy is relativley plentiful (given enough solar capture), however, materials will be much harder to come by.

One thing to note about these electrical energy calculations is that they do not take into account energy required for manufacturing. Aluminum will most likley be the metal of choice for space construction and can be mined from the moon. In order to smelt aluminum, the original designers proposed the use of solar furnaces. Solar furnaces work by concentrating sunlight using parabolic mirrors. With the energy acting over a smaller area, the light can be used to smelt aluminum. These solar furnaces may be connected to the main torus, however, it is also likley that they will be seperate satellites and not apart of the overall torus system.

|

| Fig. 3: Solar cell area vs. energy consumption. (Source: N. Martelaro) |

While modern solar cells increase the feasability of providing solar based energy to the colony, it all depends on the 3kW per captia estimate of electrical energy usage. While this estimate may be reasonable as it is double current US electricity use, it may be underestimating the energy requirments for life support in the colony. The Torus is designed to be biologically stable, with agriculture helping to scrub the air of excess carbon dioxide and to produce oxygen. However, it is still very possible and likely that external devices such as scrubbers will need to be used to pull carbon dioxide and other hazardous chemicals from the air and water within the torus.

In 1975, there was little data to be had about the energy required for life support in space. However, with the International Space Station in operation for many years, we can see what its energy requirements have been to see if 3kW per capita is a reasonable estimate. Based on a 2011 NASA report, the power systems of the ISS generate ~110kW for up to 6 astronauts. [5] This gives a per captia electricity use of 18kW, six times our estimate of from above. Keep in mind, though, that electricity generated powers all of the life support systems and the experiments on the ship. Since the ISS requires active life support, much of the electricity goes to managing air and water systems as well as onboard controls. About 30kW is available for experiments, meaning 80kW is used for general ship operations and life support. Another thing to note is that the ISS has capacity of 6 astronauts; however it is possible that more people courld suvive if there were more room (probably not too many more though). Given these real-world numbers it may be prudent to update our estamate for solar cell area if the energy requirments are not 3kW per captia. Fig. 3 shows a plot of the cell area given increasing energy requirements. This chart assumes a 22% solar cell efficiency. Given the linear relationship between consupmtion and solar cell area, we see that we reach our original estimate of 215,000m2 at about 7kW per captia. If it were to require ~18kW per person then we would require over 589,000m2 of solar cell area.

|

| Fig. 4: Stanford Torus solar array and radiator sized to scale. (Source: N. Martelaro) |

Any use of power will generate waste heat. To manage the system, a radiator is needed to expel this waste heat out into space. In the original design for the Stanford Torus, it was estimated that the colony would need to radiate 131MW of power. This value was estimated assuiming 30MW of electricity use, and 66MW of raw solar for agriculture, and 35MW for illumination and heating. The original study assumed a radiator temperature of 280 K, emitting 348.5 W/m2, and a radiator efficiency of 60%. This yields a 628,000 m2 radiator area. The design study suggested that an addition of 50% in area would help with managing peak loads, bringing the radiator to 941,000 m2. Assuming that the estimated heat from environmental sources is reasonable, then increasing the electric load from 30MW to 70MW would require an increase in area to 1.2 × 106 m2, an increase of about 27% in area.

While the estimates that we have made above provide a numberical understanding of the size of socal cell and radiator arrays required for the Stanford Torus, it can be challenging to visualize what these would look like at scale, especially as areas increase by a power of 2 given the length of a panel side.

Looking at the original darwings of the Torus, the main ring is 1800 m in diamter. The inner ring, which has solar panels appears to be about 600 m in diamter with a 200 m hold for use as a spaceport. If the entire area of the disk were covered in solar panels, there would be 251,000 m2 of solar panels. This would cover the required 215,000 m2 estimate from 1975, and would allow for over double the capacity required with modern solar cell efficiency. Even if the electric energy requirements were upwards of 70MW, the panels would have enough capacity. This being said, the available area with 22% efficient solar cells and 3kW per capita utilization allows for a factor of saftey of 2 in power generation. Given that any loss or degradation of power could be fatal in the colony, it seems prudent to have a system with double the capacity. This will allow for system to be offline due to mechanical or electrical failures and allows for growth in energy usage (within reason as the radiator can only handle so much load).

The true feasability of building and operating the Stanford Torus is still up for debate. However, this analysis, based on modern solar technology, does suggest that such a large structure in space could be supplied with electricity through onboard solar power generation. Assuming a stable mirror can be put in place, the solar array of the inner disk could provide for approximatley 2× the required electrical energy needed given a 3kW per capita usage. What is more likely to be prohibitive is the size of the radiator. At almost 1 sq. km, the amount of material required would be immense. Still, the energy is there if and can be managed if we can build the nessecary infrastructure.

© Nikolas Martelaro. The author grants permission to copy, distribute and display this work in unaltered form, with attribution to the author, for noncommercial purposes only. All other rights, including commercial rights, are reserved to the author.

[1] R. D. Johnson and C. Holbrow, "Space Settlements: A Design Study," U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA SP-413, October 1976).

[2] L. P. Gaucher "Energy Sources of the Future for the United States," Solar Energy 9, 119 (1965).

[3] P. E. Glaser, "Power From the Sun: Its Future," Science 162, 857 (1968).

[4] M. A. Green et al., "Solar Cell Efficiency Tables (Version 45)," Prog. Photovoltaics 23, 1 (2015).

[5] "Powering the Future: NASA Glenn Contributions to the International Space Station Electrical Power System," U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, FS-2011-07-006-GRC, July 2011.