|

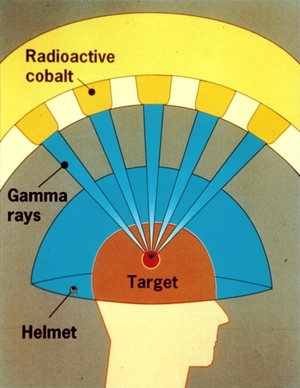

| Fig. 1: A graphic of the Gamma Knife principle. Beams of gamma rays converge at a point to deliver a lethal dose of radiation to the intended target. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

Stereotactic radiosurgery refers to one of several types of non-invasive surgical methods that use high dosages of radiation (X-rays, gamma rays, or charged particles) to precisely target and destroy lesions or tumors in the body while leaving healthy cells relatively unharmed. Multiple beams of radiation converge at the target site from many directions and deposit a lethal dosage at the target site. The process is aided by high resolution tomographic imagery such as CT scans or MRI, which help surgeons define the treatment area to millimeter precision. [1] Originally developed for treatment of lesions and tumors in the brain, stereotactic radiosurgery is now being used for a variety of tumors including those in the spine, pancreas, lung, and prostate. [1] It is regarded as a safe alternative to conventional invasive surgery and an effective method to treat otherwise inoperable tumors in the brain. [2]

Radiation has been used as a treatment method for diseases ever since it was discovered over a century ago, well before the full health effects of radiation were known. [3] The modern methods of stereotactic radiosurgery were developed by the Swedish neurosurgeon Lars Leksell beginning in the 1950s. [2] To treat brain lesions using this method, Leksell used an X-ray generator fixed to a "stereotactic frame" mounted on the patient's head. The frame fixed the location of the brain with respect to the X-ray tube. The frame also allowed the X-ray tube to be moved along an arc so that the X-ray beams would all intersect at the desired target in the brain, depositing a high dose of radiation to the target and relatively small dosages to the surrounding areas. This pioneering technique continued to develop in the throughout the second half of the 20th century into three distinct types - the Gamma Knife, Linear Accelerator (LINAC) radiosurgery, and Proton Beam radiosurgery.

|

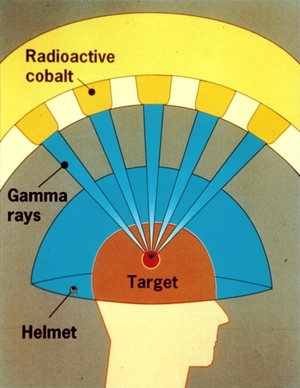

| Fig. 2: A graphic of the N-bar or N-localizer. When a tomographic image (such as a CT scan) is taken, a cross section of the N is seen. By measuring the distance between the center ellipse to the left circle, we can determine the height at which the image is taken with respect to the N-bar. Using 3 N-bars allows the reconstruction of the image plane. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

The Gamma Knife uses multiple beams of gamma rays from the radioactive decay of Cobalt-60 with an effective energy level of 1.25 MeV. [1] The radiation source is arranged in a hemispheric array and the beams are focused to converge at a single, fixed point. [4] The couch (the bed on which the patient lies on) is moved so the beams can target a region of patient's brain. See Fig. 1 for an illustration of the principles of the Gamma Knife. The first Gamma Knife was developed by Lars Leksell in 1968, which consisted of 179 Cobalt-60 beams (the modern Gamma Knife consists of 201 Cobalt sources). [1,4] The target of the treatment is localized by using the stereotactic frame device, fixed to the patient's head. MRI or CT imaging is used to locate the target and a set of "N-bars" help determine the 3D position of the target (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the N- bar). [1] The Gamma Knife is limited to treating anomalies of the brain due to the requirement of the stereotactic frame. [1] It is useful for tumors up to 4 cm in size, since larger tumors would require more radiation to be delivered to healthy parts of the brain, which could have detrimental impacts. [1]

Small linear accelerators (linac) use microwave to accelerate electrons, which then collide with a heavy metal element, producing X-rays. [1] The X-rays are collimated into a beam which then passes through the target. Typically, 6 MeV electrons are used to produce the X-rays. [1] Even though there is only 1 radiation source, the X-ray beam is directed at the target from multiple directions with precision, so the underlying treatment principle is the same as that of the Gamma Knife. Traditional linac setups use a stereotactic frame, similar to the one developed by Leksell, for target localization. However, new techniques have developed with the aid of robotics where real-time imaging (with lower-energy X-rays) is performed to track the location of the target as treatment is performed, which eliminates the need for a stereotactic frame. [1] One example of this is the Cyberknife, which uses a lightweight linac mounted on a modified industrial robotic arm. [1] Due to their flexibility, some linac-based techniques like the Cyberknife can be extended beyond neurosurgery to treat pancreatic, lung, and prostate tumors. [1]

|

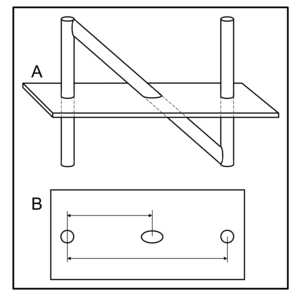

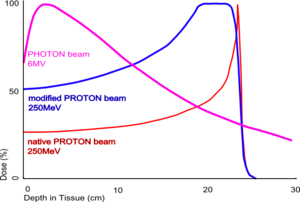

| Fig. 3: The Bragg Peak for proton beams. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) |

Another radiosurgery technique involves using charged particles, typically protons, instead of photons, to deliver the energy for treatment. The guiding principle behind radiosurgery using charged particles is the Bragg Peak (see Fig. 3), which tells us that the penetration depth of a charged particle is related to its initial energy, and that the majority of energy of the charged particle is deposited right before it reaches this depth, followed by a sharp drop-off. [1] This allows most of the energy to be delivered to the intended target and healthy tissue behind the target to receive minimal energy. Because of this, proton beam therapy has been applied to radiosensitive areas such as near the eye, where other radiosurgery techniques are considered too risky. [1]

© Rick Zhang. The author grants permission to copy, distribute and display this work in unaltered form, with attribution to the author, for noncommercial purposes only. All other rights, including commercial rights, are reserved to the author.

[1] L. S. Chin and W. F. Regine, eds., Principles and Practice of Stereotactic Radiosurgery (Springer, 2008).

[2] L. Leksell, "Stereotactic Radiosurgery," J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 46, 797 (1983).

[3] M. Schulder et al., "Historical Vignette: The Radium Bomb: Harvey Cushing and the Interstitial Irradiation of Gliomas," J. Neurosurg. 84, 530 (1996).

[4] A. Wu et al., "Physics of Gamma Knife Approach on Convergent Beams in Stereotactic Radiosurgery," Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 18, 941 (1990).