|

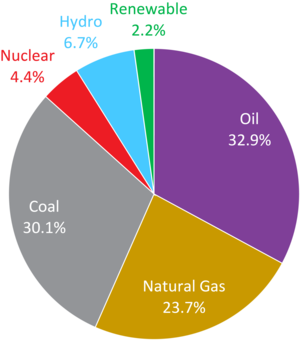

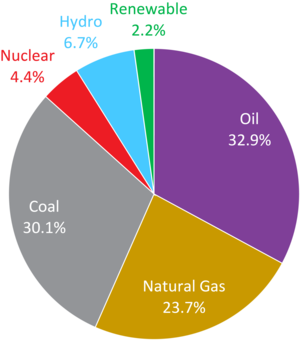

| Fig. 1: Breakdown of global energy consumption in 2013. [1] |

Of the 12.7 billion tons of oil equivalent (TOE) of energy consumed globally in 2013, oil (4.2 billion TOE), natural gas (3.0 billion TOE), and coal (3.8 billion TOE) jointly accounted for nearly 87% of the world's total energy consumption that year (Fig. 1). [1] However, according to recent estimates, continuing to consume each of these three non- renewable resources at current rates will lead to the depletion of the entirety of our planet's known reserves of oil in ~53 years, natural gas in ~55 years, and coal in ~113 years. [1] Given the alarming prospect of exhausting human civilization's primary sources of energy within the span of a few generations, the world faces a pressing need for the development of alternative energy sources.

Among the many potential candidates for alleviating the effects of the predicted shortfall of current leading energy sources are biofuels. [1-3] Broadly speaking, biofuels are energy-rich molecules that are produced by living, biological organisms. [4] Such molecules, which contain an abundance of carbon-hydrogen bonds, can come in a variety of forms, ranging from alcohols (e.g., butanol and isobutanol) to hydrocarbons (e.g., undecane) to fatty acids (e.g., fatty acid ethyl esters). [2,5] In general, the generation of these biofuels involves leveraging the metabolic processes of plants, algae, or bacteria in various ways in order to convert carbon input in the form of sugars, biomass, or carbon dioxide (via carbon fixation) to more energy-dense chemical compounds rich in carbon-hydrogen bonds. [2,5]

Plants, especially crops such as corn, have long been examined as a potential source of biofuels. [2-5] Although plant-based biofuels, such as biodiesel, have found their way to the consumer market, it turns out plants are not a practical means of producing biofuels. [2-5] Among the many limitations of plant-based biofuels are a reliance on water supplies for growing crops, the use of land which could otherwise be used for agriculture, as well as the fact that many plant-derived biofuels are not compatible for use by gasoline engines or transport via existing infrastructure. [2,4,5] These impracticalities are reflected in the quantity of biofuels generated on a yearly basis: a total of only 65 million TOE of biofuels - which are largely accounted for by plant-based fuels - were produced in 2013. [1,5] In the context of the world's vast energy needs, the current total production levels of biofuels correspond to a mere 0.5% of the net global energy consumption in 2013, and are therefore as much as two to three orders of magnitude below levels necessary to have an appreciable impact towards mitigating an impending global energy crisis. [1]

In light of significant strides in metabolic engineering coupled with the emergence of the field of synthetic biology, recent efforts have moved beyond plant-based fuels and instead turned to developing viable methods of generating biofuels by engineering algae or non-photosynthetic bacteria. [2,5-10] Much progress has been made in leveraging the approaches of these two fields, including, for instance, the recent demonstration of butanol synthesis by cyanobacteria via carbon fixation as well as the engineering of non-native metabolic pathways in Escherichia coli - which is a widely-studied, extensively-characterized, and well-understood bacterial model system - with the aim of facilitating biofuel synthesis. [2,4,5,7,8] Nevertheless, these approaches have yet to yield a viable, economical, and sustainable means of generating biofuels on an industrial scale at sufficiently high yields of product fuel relative to the quantity of precursor compounds. [2,4,5] While the fields of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology will no doubt continue gradually moving towards the goal of developing bacteria capable of large-scale, efficient production of biofuels, the recently-demonstrated capability to quantitatively model and simulate an entire cell in silico opens the possibility of leveraging such computational approaches to inform experimental and engineering efforts in vivo. [11-14]

In a tour de force of computational biology, Markus Covert's group at Stanford University reported in 2012 the achievement of the first whole-cell simulation of Mycoplasma genitalium, a bacterial parasite which manages to function on a mere 525 genes. [11,15] Without delving into the details of the model, it is worth noting its remarkable computational complexity: despite the uniquely low number of genes of M. genitalium relative to other known life forms, the development of a complete whole-cell model necessitated the incorporation of well over 1,900 quantitative parameters determined from extensive genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic experimental data sets brought together across hundreds of separate publications. [11,15] This particular model has already shown itself capable of accelerating biological discovery by identifying areas where further experimental efforts could be fruitful simply based on examining how the model and our experimental knowledge of M. genitalium differ. [11,13]

Despite this early success of whole-cell simulation in influencing experimental research, the scope of the reach and applicability of a whole-cell model of M. genitalium is limited. It turns out that this particular organism - which is not a model system - is not widely studied or used by members of the scientific community primarily due to many practical difficulties involved in working with this bacterium in the laboratory. [11,12,14] In fact, these difficulties have led to a dearth of some experimental M. genitalium data which have, by necessity, been substituted in the whole-cell simulation with measurements obtained from E. coli. [11,16] In part due to the reliance of this model on E. coli data, the M. genitalium whole-cell simulation, while extensive, has not yet reached a level where it can be viewed as a fully-predictive model. [11,15]

Although the reliability and application of the existing M. genitalium whole-cell simulation is limited, building on this work to develop a more advanced whole-cell model capable of encapsulating the intracellular processes of the model bacterium E. coli, whose genome is comprised of ~8 times more genes than M. genitalium (i.e., 4,288 protein-coding genes in E. coli), could potentially streamline metabolic engineering and synthetic biology efforts in developing engineered versions of E. coli capable of efficiently synthesizing readily-usable biofuels on a large scale. [2,5,12,14,17] Because E. coli is one of the most extensively studied organisms on our planet and reliable quantitative genomic, proteomic, and metabolic parameters are readily available, a whole-cell model of E. coli would inherently avoid many of the limitations which plague existing M. genitalium simulations. [16] Without a doubt, the development of a whole-cell model of E. coli with a level of sophistication facilitating reliable computational predictions of experimental outputs in vivo is, at present, a monumental task and is likely many years away. Nevertheless, if and when such a model does emerge, it would be possible to imagine a new approach to engineering bacteria where the effects and chemical outputs of changes to metabolic pathways are assessed quickly in silico using a predictive whole-cell E. coli model before more extensive experimental efforts are undertaken to engineer bacteria with certain desired properties. [2,5,12-14] For example, in the context of biofuels, it would potentially be possible to tweak parameters of the model to see how changes in one or several specific components of metabolic pathways might affect the yield or rate of biofuel production. This could potentially allow for more combinations of changes to be tested in silico before doing lengthier tests in vivo, thereby helping accelerate the development of more efficient and scalable biofuel- synthesizing E. coli strains.

© Bojan Milic. The author grants permission to copy, distribute and display this work in unaltered form, with attribution to the author, for noncommercial purposes only. All other rights, including commercial rights, are reserved to the author.

[1] "BP Statistical Review of World Energy," British Petroleum, June 2014.

[2] S. Huffer et al., "Escherichia coli For Biofuel Production: Bridging the Gap From Promise to Practice," Trends Biotechnol. 30, 538 (2012).

[3] G. R. Timilsina, "Biofuels in the Long-Run Global Energy Supply Mix for Transportation," Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A 372, 20120323 (2014).

[4] C. W. Schmidt, "Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Dispersants in the Gulf of Mexico," Environ. Health Perspect. 118, A338 (2010).

[5] L. S. Gronenberg, R. J. Marcheschi, and J. C. Liao, "Next Generation Biofuel Engineering in Prokaryotes," Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 462 (2013).

[6] A. S. Khalil and J. J. Collins, "Synthetic Biology: Applications Come of Age," Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 367 (2010).

[7] J. M. Clomburg and R. Gonzalez, "Biofuel Production in Escherichia coli: The Role of Metabolic Engineering and synthetic Biology," Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86, 419 (2010).

[8] E. I. Lan and J. C. Liao, "Metabolic Engineering of Cyanobacteria for 1-Butanol Production from Carbon Dioxide," Metab. Eng. 13, 353 (2011).

[9] C. E. Vickers, D. Klein-Marcuschamer, and J. O. Krömer, "Examining the Feasibility of Bulk Commodity Production in Escherichia coli," Biotechnol. Lett. 34, 585, (2012).

[10] D. E. Cameron, C. J. Bashor, and J. J. Collins, "A Brief History of Synthetic Biology," Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 381, (2014).

[11] J. R. Karr et al., "A Whole-Cell Computational Model Predicts Phenotype from Genotype," Cell 150, 389 (2012).

[12] O. Purcell et al., "Towards a Whole-Cell Modeling Approach for Synthetic Biology," Chaos. 23, 025112 (2013).

[13] J. C. Sanghvi et al., "Accelerated Discovery Via a Whole-Cell Model," Nat. Methods 10, 1192 (2013).

[14] D. N. Macklin, N. A. Ruggero, and M. W. Covert, "The Future of Whole-Cell Modeling," Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 28, 111 (2014).

[15] M. Isalan, "Systems Biology: A Cell in a Computer," Nature 488, 40 (2012).

[16] J. R. Karr et al., "WholeCellKB: Model Organism Databases for Comp[urehensive Whole-Cell Models," Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D787 (2013).

[17] F. R. Blattner et al., "Complete Genome Sequence of Escherichia Coli K-12," Science 277, 1453 (1997).